Kanky-dip’s Exile

Kanky-dip was a Tuubuutite of no renown. She had been captured by the Cave-Rippers and allowed into their society on account of her battle prowess; but she had little prowess in politics, and accordingly earned no honors. And after years of battling the rival Land-Slayer clans, and defending her caves against the raiding Ridge-Riders, she lamented that all these natha must live in perpetual war.

So she said to her kin: “If we allied with the Land-Slayers we would be safer, for they too despise the Ridge-Riders.”

“This is why you remain a lowly soldier,” said her kin. “Anyone with sense knows that the Land-Slayers would never ally with us, and if they did, their warrior Dag-nag would rouse them to rob us.”

Then a great monster appeared on the surface of Tuubuut. And the Land-Slayer Dag-nag slew the beast and spattered its stinking remains all across the land. And the stench was such that many natha fled into the mountains, and were slain by the Ridge-Riders; and others fled to the caves.

And Kanky-dip said to these Land-Slayers, “Since Dag-nag has covered your homes in filth, you are welcome in our underground caves. But first you must exile Dag-nag for ruining this domain.” And the Land-Slayers were glad to do so.

But the Cave-Rippers were annoyed at sharing their home with their former rivals. And they said to Kanky-dip, “You must find somewhere else for these Land-Slayers. They care nothing for our customs. They crowd our caves. They play bad music.”

And the Land-Slayers said to Kanky-dip, “You must find a better home for us. These caves are oppressively dark and constricting. There is nowhere to take our krikisis out.”

Then Kanky-dip was overwhelmed, and she decided to consult their ruler Sluk-Sluk. So she left the caves and braved the stench of the surface to travel to Sluk-Sluk’s holy rock pillar. And she climbed that rock pillar, though this was deadly to do. And when she summited it she found herself in a strange place with tall green things growing from the ground. That was the first time Kanky-dip saw trees.

When Sluk-Sluk noticed her he said, “How dare you sneak into my home! Explain yourself, natha.”

So Kanky-dip said, “Sluk-Sluk, holy ruler, I come to you for help. The Nargops’s corpse taints the land with its stink.”

“So you come to a Borgokog to solve your problems? Go back to the other natha. There are enough of you to fix this if you work together. But do not mention what you saw here, or you will die.”

So Kanky-dip climbed back down. And in the caves she said to her kin, “The world above shall not be ruined forever! There are many of us here, and us Cave-Rippers are the greatest diggers in the world. We shall work together to dig trenches, into which we shall bury the Nargops’s remains.”

“I will not suffer that filth to come near my person,” said a Cave-Ripper.

“And I am not a trained digger,” said a Land-Slayer.

“You are an idiot,” said everyone.

So Kanky-dip again ventured to the surface with a shovel she fastened from Tuubuut stone and steel, and she endured the stench for eight thousand days while she dug trenches and buried bits of carcass. But even after all this time only a fraction of the Nargops was buried. So she returned to the caves to request help.

But the natha were repulsed by her smell and said, “Do not befoul this place with your monster-stench! This is all we have left. Go away, Kanky-dip, and never return.” And no one came to Kanky-dip’s defense.

So she took her shovel and left Tuubuut. She did not fear the specters of the Desolation, for she no longer valued her own life. And when the specters came upon Kanky-dip, and all of her senses turned to pain, and she felt death was near, she merely closed her eyes to accept it. But then the pain receded, and the specters withdrew.

Yet as she journeyed more specters attacked, and each time Kanky-dip closed her eyes, and each time they withdrew. So Kanky-dip surmised that the specters would not attack if they could not see their victim’s eyes, for it is the eyes which the specters target.

And then she felt a sense of wonder, for she knew of no one who had survived the specters. So she thought then that perhaps her life was valuable. And she continued to close her eyes when they approached, and in this manner she traveled the Desolation for many moons until she reached the mystical Thelethy Forest.

Kanky-dip in Thelethy

Kanky-dip stared in awe at the forest for several days, wishing to enter, but feeling unworthy, and also afraid, for the trees looked like those she had seen on Sluk-Sluk’s pillar, and she knew a Borgokog lived here. And then she saw that Borgokog: Feyjiji, whose glorious form seemed to grow from the forest itself. And Feyjiji said, “What is that odor? It smells like my good friend the Gulgovx. You must be feeling better now, since you have traveled all the way from Vorgoftonk. Where are you hiding?”

Then Kanky-dip came forth from behind her shovel. “I am merely a natha,” she said, “despite my corpse-smell.”

“How have you survived the specters?” asked Feyjiji.

“I closed my eyes and they departed,” said Kanky-dip.

“That is nonsense,” said Feyjiji. “Probably some stealthily benevolent Borgokog guided your travel. Why are you here?”

“I was exiled from Tuubuut,” said Kanky-dip, “on account of my smell.”

Then Feyjiji wiggled her fingers and brought a holy rain down on Kanky-dip, and thereby cleansed her of her smell. “Now I shall take you home,” said Feyjiji.

“They hate me there,” said Kanky-dip.

“In that case you may stay here,” said Feyjiji. For she knew that Sluk-Sluk was a temperamental Borgokog, and she suspected that his natha were mistreated; and anyway she thought her own natha might like a friend. “But you must never take my natha from this domain, or I will kill you,” she said.

“I have no reason to leave,” said Kanky-dip.

So Feyjiji led Kanky-dip into her domain. And Kanky-dip was amazed to enter that forest and walk between towering trees so dense she could have touched two at once, if she had dared; but she was too intimidated by Feyjiji to touch anything. And she could hardly see the sky through the canopy above. And when Feyjiji led her past Get Grove the grass caressed her shins and soothed her weary legs. And when they passed Lindle Lake she marveled that she could see all the gerfish swimming in their bewildering way, and the femblegrass swaying at the bottom, so clear was the water; and Feyjiji let Kanky-dip stare into those mesmerizing depths for many minutes, for she was proud of her domain. And Kanky-dip was so dazzled she forgot about the natha.

But then Feyjiji led on until they heard a gorgeous voice singing the most mystical melody any natha ever heard. It was so perfect that Kanky-dip realized only after several verses that it was not one voice, but two, perfectly linked in intertwining harmonies and unisons. And then she saw the singers: two wondrous natha walking upon the tree branches. And one of them had green hair, and the other had black hair; but apart from this Kanky-dip could discern no difference in their perfect forms, which, when they stood still, seemed a part of the trees. And Kanky-dip did not notice until they finished singing that her cheeks were wet with tears, and she was embarrassed.

Then Feyjiji said, “Aetheel and Noetheel, we have a visitor.” And the two natha turned their faces to Kanky-dip in wonder, and the black-haired natha nimbly lept down the tree to stand before Kanky-dip. And she said, “Where are you from?”

“Tuubuut,” said Kanky-dip. Then the black-haired natha ran her hands through Kanky-dip’s short hair, and Kanky-dip quivered at her touch.

“This is Noetheel,” said Feyjiji.

“I am Kanky-dip,” said Kanky-dip.

“Kanky-dip!” said Noetheel. Then she repeated the name several times in different pitches and inflections. And Kanky-dip thought her own name had never sounded so lovely, though she did wonder if she was being mocked.

“And that is Aetheel,” said Feyjiji, indicating the green-haired natha who had not moved from the tree. “Kanky-dip will live here now,” said Feyjiji, “because her people hate her.”

Then Feyjiji left the three natha. And Noetheel asked, “What is that you carry?”

“My shovel,” said Kanky-dip. “I thought perhaps I might need it to defend myself, but here it seems unnecessary, unless you need to dig a hole.”

“Yes, dig a hole,” said Noetheel. So Kanky-dip dug a hole. And Noetheel marveled at her speed and strength, and she hopped into the hole, and climbed back out, and smiled and said, “Give me your shovel.” So Kanky-dip did, and Noetheel dug her own hole, but it was difficult work, and her hole was much smaller. “How did you get so strong?” she asked. And Kanky-dip told of her time in Tuubuut’s caves, and of digging the trenches.

“How did you survive the Desolation?” asked Noetheel.

“We need not speak of that,” said Aetheel, who still sat in the tree.

“But I want to,” said Noetheel, “so we will. How did you survive the specters, Kanky-dip?”

“I closed my eyes and they departed,” said Kanky-dip.

“So it is possible!” said Noetheel. “Kanky-dip, please take me away from this dull place.”

“No!” screamed Aetheel, and now she did leave the tree, and she pulled her sister away from Kanky-dip.

“You need not worry, Aetheel,” said Kanky-dip, “for I promised Feyjiji not to take any natha from this place. And there is no place I could take you anyway, for I am exiled from Tuubuut.”

“You could take me to Chut,” said Noetheel. “The Borgokog Gardragit visits often, and I have marked well which direction she departs in.”

“You will take her nowhere,” said Aetheel. Then she wept, and in our mortal world sorrowful rains flooded an entire island.

“We will stay here,” said Kanky-dip, but still Aetheel wept.

“Pay her no mind,” said Noetheel. “She is unreasonably scared of the Desolation. In a moment she will be fine.” But Kanky-dip felt guilty for bringing that beautiful natha to tears.

Then Noetheel asked if Kanky-dip would like to sing, but Kanky-dip did not know how to sing. So Noetheel asked if Kanky-dip would like to climb trees, but Kanky-dip did not know how to climb trees. So Noetheel asked if Kanky-dip would like to swim, but Kanky-dip did not know how to swim. And then Kanky-dip felt ashamed as well as guilty.

“It is no matter,” said Noetheel, “for I shall teach you all these things. They must seem frivolous to you, who have crossed the Desolation unscathed.” But to Kanky-dip they did not seem frivolous. In fact they seemed more worthwhile than anything she had heretofore accomplished, which in her mind was nothing. And in the following days she did learn to sing, though not well; and to climb trees, though not nimbly; and to swim, and at this at least she was competent. And sometimes Feyjiji joined the natha in these activities, and Kanky-dip marveled that a Borgokog spent time with her natha, for Sluk-Sluk seldom deigned to interact with his. And Kanky-dip also marveled that there were no natha here who fought against each other, for there were no other natha here at all.

One day Kanky-dip said to Noetheel, “You have taught me all these wonderful things, and I have done nothing for you. What can I offer?”

“You could take me to Chut,” said Noetheel, for her sister was not around.

“I cannot do that,” said Kanky-dip.

“Then you could teach me to dig,” said Noetheel. And though Kanky-dip doubted whether such a skill was worthwhile, she lent Noetheel her shovel and taught her to dig. And together they dug a system of tunnels so sprawling that they reached almost all parts of the forest. But each night they returned to the surface, for Aetheel could not bear to sleep apart from her sister.

And one night, as the three natha lay in the grass staring at the stars, Noetheel sang a lullaby so sweet that Aetheel and Kanky-dip both fell into the softest sleep they ever slept. Then Noetheel dragged the sleeping Kanky-dip back into the tunnels. And she shook Kanky-dip awake and said, “Kanky-dip, you must take me from this forest. I have spent my whole life in idle diversions, never knowing the world beyond, never knowing other natha, never even knowing myself– for how can I fulfill my potential if I never make my own decisions? I have no life, Kanky-dip. I have only the rules which Feyjiji binds me to. I do not begrudge her care, but I know her caution is unfounded, for you traversed the Desolation alive. If you do not take me away, I will sneak out on my own, and then I will certainly die– and a welcome death it will be.”

And Kanky-dip did not understand why anyone would want to leave Thelethy, but she saw that Noetheel was earnest. And seeing Noetheel in such sorrow was more than she could bear. So she took Noetheel’s hand and led her through the tunnels to the edge of the forest, and there she dug a new tunnel which led out to the Desolation. “You must close your eyes when the specters approach,” said Kanky-dip. And Noetheel nodded.

So they left the Thelethy tunnels, and emerged in the barren waste of the Desolation. And Noetheel stared in wonder at her feet on the dirt, a feeling she had never felt. But they did not linger, for they feared Feyjiji’s wrath. So Noetheel led them in the direction she had seen Gardragit go, until a violent wind arose and blew the dust so furiously that they could not see, and they sheltered in a hole dug by Kanky-dip. And when the winds finally relented they crawled out of the hole, and Noetheel was amazed at the clarity with which she could suddenly see the world; but Kanky-dip was wary, for she recognized this intense clarity as a sign of the specters. And soon even Noetheel was afraid, for the bright sky hurt her eyes, and the silence hurt her ears, and the air hurt her skin. “Close your eyes,” said Kanky-dip. And Noetheel did, though it did not ease her pain.

And then the specters came upon them, and Kanky-dip saw the voids of their mouths gaping in hunger, and she too closed her eyes. But the natha’s pains grew even stronger, for the specters still approached. For of course they cared nothing for a natha’s closed eyes. They had only avoided Kanky-dip earlier because she stank of the Nargops, as Dag-nag had before her. But now Kanky-dip did not stink. And soon the natha felt the specters’ faces upon their eyes, and then began the terrible soul-sucking. This was a pain unlike any they had ever endured, for it tortured their consciousness as well as their bodies, and neither was aware of anything but their own torment.

But then a furious spray of water knocked the specters away from their prey, for the Borgokog Feyjiji had come to save her natha. And she drowned those specters in the arid Desolation. Then she spat upon Noetheel and worked the wonders of the Borgokogs, and Noetheel awoke looking into Feyjiji’s eyes, just as she had when she had been born. But she said nothing until she saw Kanky-dip standing beside her, shaking and uttering strange syllables, whereupon Noetheel cried, “Kanky-dip! We have been saved.”

“You have been saved,” said Feyjiji, “from that rogue Tuubuutite’s murderous schemes. It is no wonder her people exiled her. Now she shall rot in the Desolation with half a soul, unable to harm anyone else.”

“You must help her,” cried Noetheel, “or I will never forgive you.”

“It is you who needs my forgiveness,” said Feyjiji, “and it will be hard-won, if it is won at all. We are going back home to Thelethy.” But Noetheel fell to Kanky-dip’s feet and hugged her rigid legs and wept so bitterly that Feyjiji softened, and then she spat upon Kanky-dip and restored her soul, and then Kanky-dip saw Noetheel and returned her hug. “It was my fault,” she said.

“Indeed it was,” said Feyjiji. “For disobeying a Borgokog, you should rightly be killed, and for endangering my Noetheel you should suffer far worse. Be grateful for her misplaced pity, for it has saved you in this instance. But you shall never return to Thelethy.” And Feyjiji tore Noetheel from Kanky-dip, and headed back toward Thelethy.

“How will I survive the specters?” asked Kanky-dip.

“I suppose you will have to close your eyes harder next time,” said Feyjiji, and then she took her wailing natha back home.

So Kanky-dip stood awhile in despair. Then she hid in her hole while she decided what to do. And she could think of nothing but to continue on to Chut. And she felt somewhat safer from the specters in that hole, so she decided to dig a tunnel all the way to Chut. Now you may wonder how she could dig a tunnel to a place she had never seen. Well, you remember that she spent many years digging trenches for the Nargops, and before that she had dug tunnels through the caves of Tuubuut with her fellow Cave Rippers. So she could tell her direction even in the dark. Thus she dug beneath the Desolation, surfacing occasionally to mark her progress by the meager landmarks she found.

Kanky-dip in Chut

Kanky-dip labored for many days until she saw the curving wall of Chut adorned with colorful banners blowing in the breeze. And when she came to the gate the guard said, “Who approaches?”

“I am Kanky-dip of the Desolation,” said Kanky-dip.

“Oh my,” said the guard, for he had never heard of a natha living in the Desolation. “What is your purpose here?” he asked.

And for a moment Kanky-dip did not know what to say. Then she settled for, “I seek a home.”

“That is probably fine,” said the guard, and he opened the gate.

Within Kanky-dip found a gorgeous town with buildings whose bricks were not mud, but stone, painted in a pleasant palette; and garden paths between them, and trees throughout; and beyond this a majestic castle on a hill. And all around were natha, each of them beautiful, wearing exquisitely crafted clothes of fabrics she had never seen, embroidered with intricate designs. And all of them had lovely long hair. But they were somber, and lent their perfect voices to a dour melody almost as gorgeous as the Thelethytes’. And hearing it Kanky-dip almost wept.

Then she noticed one of the Chutters staring at her, and then he looked away and rubbed his fingers together. So Kanky-dip approached him, though he was clearly uncomfortable with her presence; and she said, “What are they singing?”

“A lament for Dooble,” said the natha. “He is the loveliest boy in the land, adored by all, but he has been imprisoned in Gardragit’s castle for battling the beast which terrorizes Chut.”

“Why is such bravery punished?” asked Kanky-dip.

“Our ruler Gardragit loves the monster,” said the natha.

“So she is as cruel as any other Borgokog,” said Kanky-dip.

“Oh, no!” said the natha. “Gardragit is kind and fair and wise in almost all matters. But in the matter of the Churbn she is confused. I believe she is hypnotized by its hissing. And so lovely Dooble languishes in a dungeon.”

“I can tell by the singing that he is a noble natha,” said Kanky-dip. “I am sorry that you have suffered this loss.”

“And I never got a chance to paint him,” said the natha. “His portrait was to be my masterpiece, the bravest and most beautiful Chutter gracing my canvas. But alas, his beauty cannot be recreated from memory, for memory falls woefully short of his living greatness. But we cannot disobey a Borgokog, so I must find other subjects. I am Brivwith, the painter.”

And Kanky-dip said, “I am Kanky-dip. My home was destroyed.” For she was too embarrassed to admit that she had been exiled.

“Kanky-dip,” said Brivwith, “yours is the strangest face I have ever seen. Would you sit for a painting?”

And Kanky-dip was uncomfortable to be seen as a curiosity, but she did not want to disappoint Brivwith, so she agreed. Thus Kanky-dip became the first Tuubuutite to be painted by a Chutter. After a week the painting was finished, and Kanky-dip marveled to see her likeness depicted with such style. Then Brivwith said, “Thank you for modeling this past week. I wish you well on your next endeavor. Goodbye!”

“May I stay with you awhile?” asked Kanky-dip.

“Ah, no, it would be improper for a Tuubuutite to live with a Chutter,” said Brivwith.

So Kanky-dip went back out into Chut and suffered the stares of the Chutters, until she noticed a group of them walking into an ornately decorated building larger than its neighbors. And following them she entered an extravagant theatre. So she sat and watched a play which she found excessively long and exceptionally dull. And afterwards a natha in ruffled garb approached her and said, “How did you like the play?”

“It was good,” said Kanky-dip.

“It would have been better,” said the natha, “if Dooble were in it. Every seat would have been filled then, with dozens standing in the back, just to watch Dooble without impropriety. But alas, he is imprisoned. Yet I expect you could draw a decent crowd, not with your beauty of course, but with your oddity. I could put you on the stage and make you famous, for I am Jroopan, the owner of this theatre.”

“Would you give me a place to stay?” asked Kanky-dip.

“You could sleep in the dressing room,” said Jroopan.

“What must I do?” asked Kanky-dip.

“Simply stand where I tell you,” said Jroopan. “You needn’t have any lines.”

So Kanky-dip agreed, and for a month she lived in the Simpaddul Playhouse, and she played a speechless Tuubuutite warrior in their next play, and she did not comment on any of the many inaccuracies in the script, and Jroopan did not request her input. And all the Chutters murmured when she appeared on stage. And when the play closed Kanky-dip left the theatre, and again wandered the domain.

She came at length to Laer Pond, where she saw a lone natha casting stones into the water. And they seemed so sorrowful that Kanky-dip thought she might relate to them, so she approached and asked what ailed them. “I am alone,” said the natha, “for my lover Dooble was taken from me. I had found happiness at last, and now it is gone forever.”

And Kanky-dip did not reply, but decided then to rescue this Dooble, for perhaps then the Chutters would accept her into their lives. So she took her shovel of stone and steel and left the domain through the gate. And the Chutter guard asked where she was going.

“Down,” she said. And the guard did not question her further, for a person with short hair and a shovel is too intimidating to interrogate.

So Kanky-dip traveled some way into the dusty Desolation, and then turned her shovel against the ground and dug a tunnel which ran underneath the Chut wall and continued all the way to the innards of Castle Hill, until she struck the wall of Dooble’s dungeon. For the Chutters spoke so often of Dooble that Kanky-dip had gleaned exactly where he was. And when her shovel struck the stone wall she battered until the bricks crumbled, and a hole appeared. Now you may wonder how someone could destroy a castle wall with a shovel. Some say that Feyjiji’s reviving magic had inadvertently imbued Kanky-dip with mystical strength. Others say that Kanky-dip’s years digging the Nargops trenches had made her an unstoppable digger. But that is a myth.

In the event Kanky-dip broke a hole into Dooble’s dungeon. And she saw Dooble there, radiant even in the darkness, his body exquisite even under his dungeon-rags, the stone beneath him beautiful simply by its proximity to his glory. And his face, when he turned it toward Kanky-dip, filled her with such awe and desire that for several moments she could only stare in silence, shovel still poised for another strike.

So it was Dooble who spoke first, saying, “I have been entreated by the loveliest natha of this domain, but your bizarre visage in this prison is the finest face I have ever seen. Who are you?”

“I am Kanky-dip of the Desolation,” said Kanky-dip. “I am here to rescue you, Dooble.”

“Have you slain the Churbn?” asked Dooble.

“No,” said Kanky-dip.

“Then my people are not safe,” said Dooble. “Will you join me in battling the monster? No, I cannot fight it again: Gardragit would kill me then.”

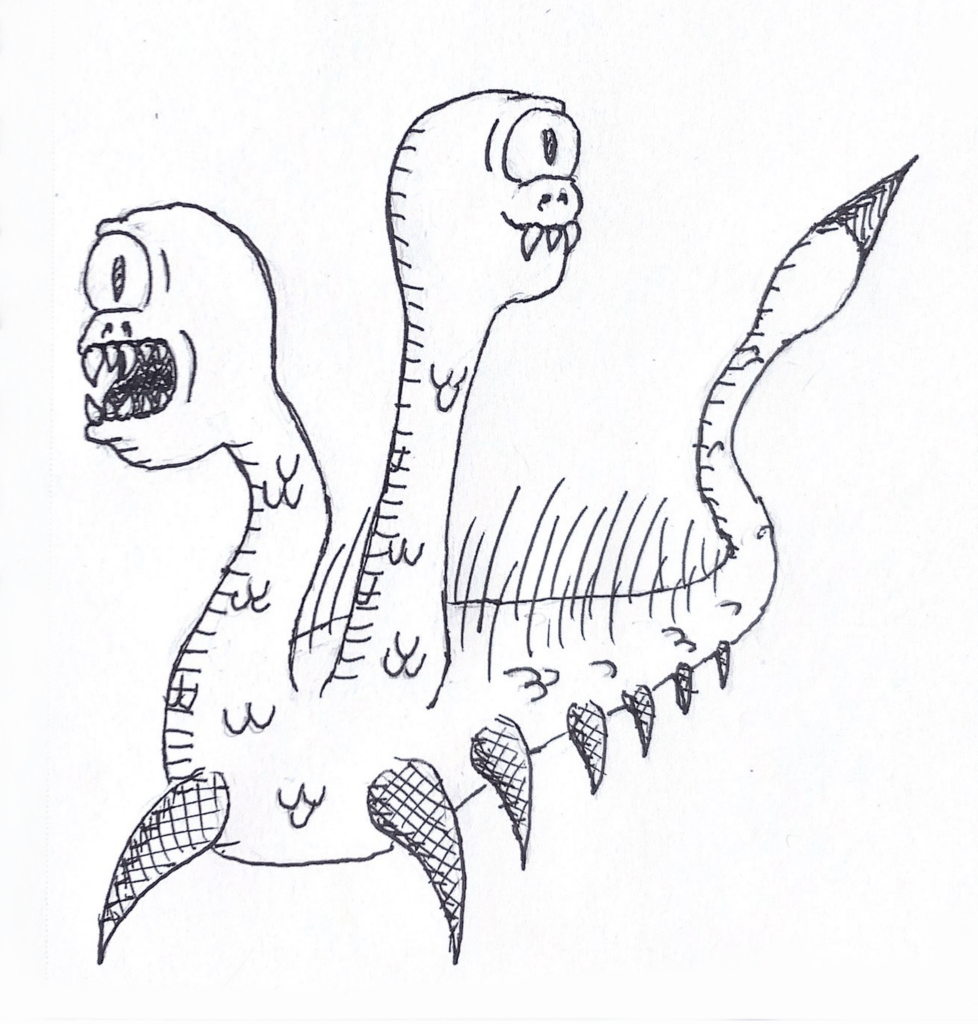

“I will battle the Churbn,” said Kanky-dip. She did not say this because she wanted to help the Chutters, but because she wanted to please this perfect natha. And Dooble’s eyes shone at these words, making his face even lovelier. And he said, “Perhaps I have finally found a true adventurer! I regret that I cannot accompany you in battle, but I can tell you about the beast. It lives in the Tookke Forest, and haunts a great hill there. You must avoid its two heads, for their jaws can crush any natha; but you must also avoid its tail, for the stinger will paralyze anything it pierces.”

So Kanky-dip left Dooble in that dungeon to go fight the Churbn. And Dooble covered the hole with his clothes, lest a guard see something awry.

Then Kanky-dip dug a new branch in her tunnel which led to the Tookke Forest, for her judgment of distance was expert even underground. And she knew she had arrived when she saw the Tookke-roots. So she dug to the surface and emerged among the whispering Tookke-trees.

Then a furry little vingum scampered up to her and squeaked something incomprehensible. “Leave me, little creature,” said Kanky-dip, “for mine is a dangerous path.” But the vingum did not heed her, and instead climbed up her legs and bit her. She shook it off and continued on her path, but again the vingum bit her, this time on the foot, so she kicked it away. Still it persisted, darting to and fro, climbing on her and biting wherever it could, until the exasperated Kanky-dip flinged the thing to the ground and crushed it with her shovel. “Small things would do well not to provoke the wrath of more powerful beings,” she said. But the Tookke-trees whispered in fury at the killing, filling the air with their indiscernible curses.

Then Kanky-dip walked farther into the woods until she found the mound that Dooble had mentioned. And she circled the hill, but found no monster; so she climbed the hill, and still saw no beast. So from her vantage on the hilltop she surveyed her surroundings, but could discern little in the darkness between the trees. “Churbn!” she called. “Come and fight me.” But the Churbn did not come. “Very well,” said Kanky-dip. “I shall destroy your home.” And she turned her shovel against the hilltop and began displacing the soil, and after a minute the hill was half as high as it had been before.

Then she heard a bestial moan in the distance, followed by a horrid hissing; and looking to its source she saw the treetops swaying out of the monster’s path as it approached. Then Kanky-dip saw two heads emerge from the woods, both bobbing angrily upon their twisting necks, and both bearing only a single eye; and then she saw its slithering body with antennae all along its surface; and as it drew near she marked well the deadly stinging tail. And Kanky-dip held her shovel in preparation for battle.

The Churbn reached her with startling speed, and when it hissed she felt the spit and saw the teeth of both its mouths. Then with one head it lunged at her with open jaws, but with her shovel Kanky-dip struck that head so forcefully that it fell back with a horrible whimper. Then Kanky-dip swung furiously at the other head, but it dodged each of her strokes, until with its dazed head it knocked Kanky-dip away, and she barely kept her footing.

Then the Churbn skittered away and climbed a Tookke-tree, its many feet clinging effortlessly to the tree-scales. And when it reached the canopy above it leapt from the branches down to where Kanky-dip stood. But Kanky-dip hurled herself out of its course, and collided with a nearby tree. So she avoided a crushing death under the Churbn.

But the tree she had struck whispered an angry oath intelligible only to leafy things, and its trunk secreted a sap that glued Kanky-dip to its scales. For it knew from the voices of its neighbors that she had murdered a vingum, and it wanted to see her slain. Kanky-dip struggled mightily to free herself, but succeeded only in dropping her shovel. Then she watched the Churbn approach her, and could do nothing to avoid it.

“Perhaps it is better to die here than to live unloved among strangers,” she thought. But this thought was not enough to allay her fear, and she dreaded the pain of being devoured while she lived, and tears of terror coursed down her cheeks as the Churbn neared. And it hissed with both heads as it prepared to strike. But the Churbn did not strike. Instead it stared at her unmoving form and moaned. Then it twisted its body until its stinging tail poised to attack her. But still it did not attack; it merely moaned again in anger.

But then its tail did strike, but not at Kanky-dip: the stinger struck above her head and pierced the Tookke-tree. Then the tree stiffened, and the sap became hard and brittle until it broke, and Kanky-dip was free. For the Churbn would not kill a foe who could not fight. It backed away from Kanky-dip and watched her grab her shovel, then awaited her next move.

So Kanky-dip approached the monster in a circling way and tried to strike its body, but always the thing would twist away and attack with its heads. And then it knocked Kanky-dip to the ground, so it was all she could do to block its attacks with her shovel; and she defended herself then with such strength that the beast bruised both jaws against that tool; and when it tried to paralyze her with its tail it bruised this as well. Then it moaned and backed away from the prone natha and circled around her, plotting its next strategy. And it turned away to climb another tree.

And Kanky-dip could think of nothing but to hide, so she dug a hole where she lay, deeper than the Churbn’s necks could penetrate, and sat in the dirt and darkness underground. Then she heard furious moaning above, and then the terrible thud of the monster landing, and then she saw one of its eyes staring down at her. So she dug a tunnel branching off from the hole so the Churbn could not see her. Then she felt cowardly indeed. And the Churbn was furious that its foe had fled from battle. So it waited awhile at the hole, but then feared she might burrow away, so it tried to follow her into the hole. But the tunnel was too narrow; and the Churbn’s attempts to widen the hole were frustratingly slow, and it knew she would outpace it.

So it moaned in fury, and then skittered up to its hill to get a vantage and perhaps see where she had fled. But as it looked about from the hilltop it felt a sudden terrible pain in its underbelly, an agony that grew and spread deep into its guts, and then it felt its back burst open as Kanky-dip emerged from the gruesome tunnel she had dug through the Churbn’s body.

Then Kanky-dip leapt down from the beast’s back covered in its gore, and watched the creature writhe and shriek; and she felt a great pity for the creature she had so dishonorably slain. For to kill an unsuspecting enemy is great shame to a Tuubuutite. And this was an enemy who had refused to fight ignobly. So she said to the Churbn, “You deserve a better death than I have dealt you, Churbn. If you will cross your necks, I shall strike off both heads in a single stroke, and end your suffering.”

And the Churbn, who spoke no natha tongue, nevertheless crossed one neck over the other, and looked pleadingly at Kanky-dip with both heads. So Kanky-dip touched each muzzle in turn, and raised her shovel and brought it down where the necks intersected, and quickly cleaved them apart. And then the blood flowed so freely down the hill that it resembled the Bloodstream Nanti of Vorgoftonk, where the Churbn had played in its younger years.

Then Kanky-dip took one of its heads as proof of its death, and would have taken both, but she could not carry both. And she returned through her tunnel back to Dooble’s dungeon and deposited the Churbn’s head before him. And Dooble smiled at Kanky-dip, and she hoped his affection was worth the murder she had done. Then Dooble said, “Together we will show the Chutters that our home is safe.”

So together they left the dungeon through the tunnel with the monster’s head. And when they emerged into Chut Dooble cried, “The Churbn is slain! Live your lives without fear, for the Churbn lives no more.” And all the Chutters recognized Dooble’s voice and hurried from their homes to see him. And when they saw not only Dooble freed from the dungeon, but also the severed head of the beast, there was such rejoicing that you would have wept to hear it, as many of them did. “How did you slay the monster?” they asked.

“I did not slay it,” said Dooble. “It was this noble adventurer Kanky-dip who killed the Churbn.”

“You are forever welcome in Chut, Kanky-dip!” said the Chutters. And Belvord the musician improvised a song for Kanky-dip and Dooble right there.

But by then the Borgokog Gardragit had heard the commotion, and came to see what was about. And when she saw her Churbn’s lifeless head she wailed with a devastating grief. “Who has killed Churbn?” she cried.

“It was Kanky-dip,” said the Chutters.

“Murderous Tuubuutite!” yelled Gardragit. “You shall suffer as poor Churbn did, and you shall die an even fouler death.”

“No,” said Dooble, “for Kanky-dip is a foreigner, and accordingly does not fall under your jurisdiction. And anyway, she slew the beast at my command.”

“Then I shall kill you as well,” said Gardragit, “as I should have done before. Alas, dear Churbn! You would live still if I had not been swayed by these natha to reject justice. Come forth, Dooble and Kanky-dip, and meet your deaths.”

“Do not kill Dooble!” the natha cried. “We will live in eternal misery if he is slain.” And they wailed and pled with such passion that Gardragit said, “Fine! Their deaths would do nothing to restore Churbn’s life, warranted though they are. I will not condemn my misguided natha to unhappiness, as these two have condemned me. But neither will I suffer them to remain in my domain. Dooble and Kanky-dip, I exile you both from Chut.”

“Please do not exile Dooble,” said the Chutters.

“It is done!” cried Gardragit. “Now leave before my mercy is exhausted.” So all the Chutters wept as Kanky-dip and Dooble left Chut. And standing in the Desolation Dooble said to Kanky-dip, “Chut is not much fun anyway. Let us go to Thelethy! I hear that is a place of great mystery.”

“I am exiled from Thelethy,” said Kanky-dip.

“So you have been there!” said Dooble, amazed. “Well, it is probably a dull place if you left. Anyway, Gardragit goes there sometimes. Let us instead go to your homeland!”

“I am exiled from Tuubuut,” said Kanky-dip.

“You have done many infamous acts indeed,” said Dooble. “And you will do many more with me by your side. Do not worry, for together we will have glorious adventures wherever we end up. But how will we survive the specters of the Desolation?”

“I will dig tunnels,” said Kanky-dip.

“Tunneling!” said Dooble. “I can tell we will have great fun together. Only I hope you will allow your hair to grow longer in the coming months.”

Leave a comment